Since I haven't used Poser in a while this is going to have less in the way of concrete examples. Also, the last version I used was 9 and it is up to 11 now. Poser tends to maintain backwards compatibility with previous tricks, though, even as it adds new ones (each generation of figures adds some new tricky way to deal with the perennial core problems like poke-through -- and let's not even get into DAZStudio which, while maintaining a large degree of compatibility with Poser-generated content, changes many of the paradigms).

So I will try to give examples, but, really, the best way to do this is to find a Poser file and reverse-engineer it. See how the stuff is actually formatted. Or go look online for one of the various useful guides. Once you know what is possible and what people tend to call it, it is a lot easier to find help on getting it right.

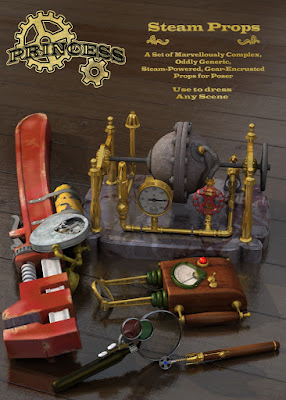

So to it. The three Poser power tools I find the most useful for the Poser content I've created over the years are, in no particular order, altGeom, ERC, and MAT poses.

altGeom:

Overview:

Way back in the early days of Poser, either the riggers, the software, or the projected customer base couldn't handle the idea of rigging every finger. So they created a way to swap out one pre-posed hand with another. The code was still in there when the first Millenial Figures arrived (the original Victoria 1 and Michael 1), and stayed in the code as the vestigial gen/noGen switch (aka, a way to change out the lower-torso mesh to one with or without the naughty bits).

altGeom is a handy way to change the shape of an item past what morphs allow you to do. Let me review for a moment; a morph is a list of deltas -- differences in position -- for the vertices already in the mesh. Applying a morph causes each vertice in the original mesh to move to a new position. Which is why you can dial in a morph as a percentage, including applying it extra strength or negatively -- in the latter, the vertices simply move in the opposite direction.

It is hard to see in that tiny video but the spring on the kick pedal here is using a morph to elongate. There are also morphs on the head of the drum so it "dimples" when hit.

For the stage microphone set I made, every stand was equipped with an altGeom dial that provisioned it with either a standard mic clip, a large shock mount, or a null object (no clip at all).

Construction:

An altGeom consists of two things; a geometry reference to the different geometry, and the code to create the dial (which is subtly different from that used in a translate or morph dial).

Again to review; in all Poser figures and most props, you will find two pointers; the figure reference file, and the actor pointer. They look like this:

figureResFile :Runtime:Geometries:Princess:Stage_Mics:shortStand.obj

and

actor clipBase:8

{

storageOffset 0 0 0

geomHandlerGeom 13 clipBase

The name you see there, "clipBase," needs to appear as a geometry group within the geometry file "shortStand.obj" The actual actor name, however, does not need to match; the geomHandlerGeom reference is the only place in Poser where it needs to see the actual name in the geometry file.

So...unlike everywhere else in the Poser universe, in a part with an altGeom there is an additional figure reference occurring inside the body of the actor;

alternateGeom clipBase_2

{

name clipBase2

objFile 2101 :Runtime:Geometries:Princess:Stage_Mics:clipBaseALT.obj

}

defaultGeomName clipBase_1

This is, of course, the actor in which occurs the actual dial for the altGeom. Take note of the "2101" there; this is a unique identifier that must be different from any other geometry used in the Poser scene. Starting above 1000 is strongly recommended.

And here is what the actual dial looks like:

geomChan handGeom

{

uniqueInterp

name change clip

initValue 0

hidden 1

forceLimits 1

min 0

max 2

trackingScale 0.045

keys

{

static 0

k 0 0

}

interpStyleLocked 1

valueOpDeltaAdd

Figure 8

clip:8

changeClip

deltaAddDelta 1.000000

valueOpDeltaAdd

Figure 8

BODY:8

changeClip

deltaAddDelta 1.000000

}

Something to note here; the limits are set to the number of actual geometries being referenced (including the original). "handGeom" must be used as the internal name for Poser to understand the unique nature of this dial, but the external, user-facing name can of course be of your choice.

Wrap-Up:

So -- a few other useful things here. The source file can contain other groups, and multiple figures can access the same alternate geometry. You can access the same group multiple times, too; I coded up but never got around to releasing a Climbing Wall where each potential hold was an actor containing the translate instructions to move the geometry into the right location on the wall. Thus, there was only one of each hold ever constructed; the cr2 did all the work of populating the wall. And, of course, the end user could set a new route merely by rotating a few dials.Unlike morphs, the altGeom does not need to share the number or winding order of vertices. However, if the edges are nearly identical, Poser will still manage to weld the meshes together when it makes a figure. Also, of course, the morphs for one geometry won't work on the other. But, strangely, Poser will sometimes recognize this and will hide the dials belonging to one geometry and show dials you've created for the alternate geometry. This can not, however, be always trusted.

Alternatives: Instead of using an altGeom, some props are simpler to build by hiding the optional bits using the ability to hide (and not render) a specific actor. As far as I know you can't build a "show/hide" dial, but you can construct a one-click pose to do it. Similarly, translate and/or scaling could be used in an ERC dial to hide one optional bit and show a different one instead.

ERC:

Overview:

When Poser finally got around to adding fingers, they realized folding all of them individually to make a first was a pita. So they added a bit of code which is still in there; name your fingers with the same internal names as those on a standard Poser figure, and create a dial called "grasp," and they will all respond to it.

It actually worked on this cute guy, here, even though he only has two fingers on each hand! Well, this same trick was later leveraged in by the Poser designers to allow all the body shape morphs to be collected together in a single spot instead of having to go to every limb and digit turning dials individually.

In any case, it didn't take long for the community of Poser tinkerers to realize that this lowly bit of code had untapped powers. In essentials. and with some important exceptions, every dial in Poser can be slaved to another dial.

This is...absurd. Some users attempted to make sense of this cornucopia by coining the terms "JCM" for morphs that automatically dialed themselves in when a joint was moved (aka, bend the elbow on a Poser figure and the biceps muscle swells in a natural way), "JCT," "FBM" (Full Body Morphs, meaning a single dial will tweak in separate "muscular" morphs across multiple body parts), Super-Conforming, etc. But in general the blanket term "ERC" (for Extended Remote Control) is accepted.

Superconforming:

One of the uses to which ERC has been put is to allow clothing to magically take on the same morphs being applied to the figure below. The trouble with this happy picture being crosstalk. A simple search will turn up thousands of systems for fixing the crosstalk problem. They are all wrong. Simply put, Poser creates instancing on the fly as figures are added to the workspace, or as a scene file is read in. It is entirely impossible to force Poser to observe unique identifiers (outside of, perhaps, manipulating the Poser workspace in a more direct way using Poser Python tools).

So you can get superconforming or crosstalk to work for you once, say when creating a scene, but save it and restore, add something new, or even work on it too long and the references will be lost.

Poser is dumb. It looks in the first place it thinks of to find anything, from the matching master dial for an ERC slave code to the correct texture file. And it doesn't always start where you would expect or want it to start. Which means that even internal ERC channels can get "lost" and wander off when you have more than one figure in the scene.

That said, operating ERC between figures is an alarmingly powerful too with all sorts of wonderful potential.

Construction:

An ERC chain consists of three things; a slave dial, a target dial, and the code within the slave dial setting how it is to respond.

The master dial can be any kind of dial; a morph dial, a translate dial...or an empty dial. The code for creating a dial that doesn't do anything itself is as follows:

valueParm turnClip

{

name turn clip

initValue 0

hidden 0

forceLimits 1

min -360

max 360

trackingScale 0.2

keys

{

static 0

k 0 0

}

interpStyleLocked 0

}

The usual dial functions are here; internal name versus displayed name, the ability to hide the dial, and, yes, dials can be stacked (just don't point them at each other. Quickest way to crash Poser that has yet been discovered).

The code that makes the magic happen is all in the slave dial:

rotateZ zrot

{

name tilt clip

initValue 0

hidden 0

forceLimits 0

min -90

max 100

trackingScale 1

keys

{

static 0

k 0 0

}

interpStyleLocked 0

valueOpDeltaAdd

Figure 8

BODY:8

tiltClip

deltaAddDelta 1.000000

}

The key is in those last four lines. The source figure is, as I said, bollixed in by Poser when you load the figure. But you can at least try to push it in the right direction by making it match the actor numbers of the figure file. The next is the actor that contains the master dial, and the penultimate is the internal name of that dial. The last is the tracking scale.

Setting the tracking right is often key to getting ERC working right. For a full body morph, the tracking is usually 1=1; each body part morph dials up to the same amount. For trying a morph to a joint rotation, though, you need to know that Poser uses 1.0 as meaning a morph is full-on, but a rotation around a full circle appears in the Poser code as "360."

So, yes; one of the most useful functions of this is to take dials that might be spread all over the figure and mirror them in a place where they are easy to find. Incidentally, another Poser peccadillo it is doesn't always save channels in the BODY when the file is saved and retrieved. It is safer to consolidate your master dials in the top selected body part instead.

But since you can merge and stack dials, there's some fun tricks you can do:

Again, sorry for the poor render here. These are actually copies from stuff I uploaded to YouTube years ago. So there's some simple things here; the turning sense head on the ghost detector is linked to a morph that extends the loop of wire connected to it. The jaws of the steam powered monkey wrench automatically spin the nut as they are opened.

A little more tricky, the gear box is set to a single dial (and all the individual gears are hidden in the cr2, meaning they display in the workspace and render but don't show up as selectable body parts), and each uses a deltaAddDelta tuned to its diameter so the teeth mesh.

A little more tricky, the gear box is set to a single dial (and all the individual gears are hidden in the cr2, meaning they display in the workspace and render but don't show up as selectable body parts), and each uses a deltaAddDelta tuned to its diameter so the teeth mesh.The trickiest is the steampunk sonic screwdriver (which is unfortunately impossible to see clearly in the render). The trick here is joint limits are set on the joints, dial limits on the dials, and in some cases a dial is set to a negative number below the joint limit. So what happens is that dial waits until the master dial has rolled it over into positive numbers again.

Under a single master dial, the spinner makes a half-turn as it starts to retract. The spring collapses with it. When it has fully retracted it stops; the leafs, which have been waiting quietly the whole time, close over it.

People have used this sort of trick...multiple stacks of dials pointing at each other, phantom dials that are hidden from the user and exist only to delay a following action... to rig tank treads.

As one extended example of ERC in action, the Easy-Pose cables or tentacles use ERC to make a long flexible object possible. The figure has an otherwise uncontrollable number of body segments, but the dials are all collected into master dials at the head so they all turn together. And you can get trickier; if each segment, for instance, takes orders from the previous segment instead of the master, and each is set to a deltaAddDelta of slightly more than 1.0, then the cable will coil into a decreasing diameter nautiloid spiral.

MAT Poses:

General:

By itself, the MAT Pose is simply a pose file that applies texture instead of joint rotations. But this is just a glimpse into what is actually possible.

The big thing to know is that there is only one syntax for Poser files. The suffix to a file; pz3, cr2, hr2, etc. tells Poser what to expect from it, but the markup language inside is the same stuff. Now, there are restrictions. Among other things, pose files expect to find a figure and will apply themselves to the last selected figure in the workspace. Bad things happen if there isn't one (this is one of the reasons why figures are a superior way to format complex props.)

In a similar way, a prop (pp2) can be told to attach itself to a figure (smart prop style) but other file types don't usually get this as an option.

The other key thing to remember about this all is that unspecified channels preserve the original data. So a pose file meant to only change expression should have all joint rotation and body morph channels edited out of it. If the channel isn't in the pose file, it won't be touched by the pose file.

Construction:

The basic MAT pose file looks like this inside:version

{

number 4.01

}

figure

{

material plastic

{

KdColor 1 1 1 1

KaColor 0 0 0 1

KsColor .2 .2 .2 1

TextureColor 1 1 1 1

NsExponent 40.4078

tMin 0

tMax 0

tExpo 0.6

bumpStrength 1

ksIgnoreTexture 0

reflectThruLights 1

reflectThruKd 0

textureMap ":Runtime:textures:Princess:PTbeltFpatrol.jpg" -1 10105

bumpMap NO_MAP

reflectionMap NO_MAP

transparencyMap NO_MAP

ReflectionColor 1 1 1 1

reflectionStrength 1

}

There are no channels specified, no actors. All it has is a material; whatever is included there will replace the material that was loaded from the cr2.

Of course it doesn't stop there. A simple pose file can also include a function that hides a body part (useful for tight-fitting shoes that would otherwise poke through):

{

version

{

number 4.01

}

actor rFoot:2

{

name rFoot

off

}

actor rToe:2

{

name GetStringRes(1024,53)

off

}

A pose file can also add new control channels, and even add morphs -- the latter, however, requires that empty hidden dials be already in the cr2 waiting for morph deltas to be attached to them. I monkeyed around a little with a slaving code that made the figure the pose was attached to mimic the motion of an existing figure in the scene. Tricky to actually work with, though -- as explained in crosstalk above!

Another odd function of MAT poses is that you can replace materials on an actor-by-actor basis;

actor rButtock:2

{

customMaterial 1

material SkinBody

{

KdColor 1 1 1 1

KaColor 0 0 0 1

KsColor 0.0554971 0.149996 0.061799 1

TextureColor 1 1 1 1

NsExponent 9.65048

tMin 0

tMax 0

tExpo 0

bumpStrength 1

ksIgnoreTexture 0

reflectThruLights 1

reflectThruKd 0

textureMap ":Runtime:textures:Princess:PThoseHarper.jpg" 0 0

bumpMap ":Runtime:textures:Princess:PThoseSherwoodBUM.bum" 0 0

reflectionMap NO_MAP

transparencyMap NO_MAP

ReflectionColor 1 1 1 1

reflectionStrength 1

}

}

This is a tricky pose here. Incidentally, the tradition was to name poses MAT if they changed materials, INJ if they injected morphs, and DIV if they used custom materials. Anyhow, for some reason Poser requires you define the material at the top of the pose file in addition to doing so within the individual actors.

So yes; this specific example put hose on the legs of the figure in question while leaving alone the skin (and eye and teeth and so forth) textures already applied. The one disadvantage is that it splits along the actor seams, although some Poser figures were specifically sliced to make those divisions fall in more useful places.

Wait There's More:

Point At:

This function can be called in the cr2:

pointAtParm Point At

{

name Point At

initValue 1

hidden 0

forceLimits 1

min 0

max 1

trackingScale 0.005

keys

{

static 0

k 0 1

}

interpStyleLocked 0

pointAtTarget bRivit:9

}

Notice that this looks just like a dial definition. In fact it is a dial. But it has to have the exact internal name Point At in order to work. The way this trick worked in the final prop; this was a stand with legs that folded up. Each leg had a brace with the center of rotation set at one end and the primary axis running the long way. When a master dial was turned that rotated each leg into the stowed position, each brace would pivot freely to keep their other end as close to the connector as they could. The result was it looked like the braces were mechanically part of the assembly.

A trick B.L. Render worked with was to Point At a "gravity ball" moved to a location far below the picture frame. That would make fringes hang down, towards "gravity." I've used a similar variation; set both eyes to Point At a hovering non-rendered ball, and you can direct the figure's gaze in a natural way.

Deleting RHA's

As B.L. says, children effect their parents. This can be a particular problem for mechanical props. Twist a knob on a control panel, and part of the panel twists up to follow. You can turn off deformation by setting "bend" to 0, but this means you can't apply morphs to that actor anymore. You can tweak the joint params to try to exclude the body part but even with zones this isn't always possible.

Or you can go into the cr2 and delete the channels that make this happen. Once deleted, Poser won't put them back (at least, not as of the last version I've used).

These channels are easy to recognize; their names have a similar format and they always include the child part:

twistY lBunear_twisty

{

name lBunear_twisty

initValue 0

hidden 1

forceLimits 0

min -100000

max 100000

trackingScale 1

keys

{

static 0

k 0 0

}

interpStyleLocked 0

otherActor lBunear:4

matrixActor NULL

center 0.0162426 0.67091 0.00326313

startPt 0.657258

endPt 0.754053

flipped

calcWeights

}

But here's another interesting thing; you can ADD these channels in order to make a control object. This is a technique called Body Handles. Adding a body handle is surprisingly easy. Add an actor in the definitions and the body of the cr2, referencing a custom geometry file for it. Add it to the hierarchy definitions neat the bottom of the cr2. Load the figure, then save again. Poser will fill in the rest of the Actor section.

Now you have a handle you can pick up and drag around that will drag part of the figure with it (depending on how you set the zone of effect). It's like a magnet that stays attached.

Translation:

Anyone who has gotten this far probably knows this one. Translation along the xyz axis of a body part is already in Poser, it is just that the dials are hidden by default. All that is necessary is to set Hidden to false for that dial. Set limits, and you have a sliding drawer or piston or whatever.

Inlychain:

I really don't remember how to work IK magic now. I do know you can get some fantastic results from it. The normal figure hierarchy works down from the BODY. If you rotate the shoulder, the forearm and hand are moved to a new position. If you rotate the forearm, the hand is moved to another new position.

Inverse Kinematics, well, inverts this. Most Poser figures have IK available for both feet; turn it on, and moving the foot drags the body parts upstream of it. So you can actually create a cable that is attached at both ends, and with the proper balancing of IK weights, it will be tugged at from both ends and attempt to shape itself to follow both.

My hi-hat stand has IK in it. Somehow I used that to allow a chain-drive going over a cam to follow everything else when you pressed the pedal down.

Conclusion:

I hope some of this helps someone. I've largely stopped creating Poser content, and all those skills that took so long to learn are going to waste now. Unless I can use them to help someone else.

"Unless I can use them to help someone else."

ReplyDeleteAnd well you can sir. The folks reading your older Poser tuts are likely following the links from my tutorial. I'd love to see you stick all your Poser material into a PDF and dump it on BagginsBill's website for safe keeping. I'm sure I'm not the only one who refers to your work. Thanks for sharing your knowledge.

Bob