(Ariadne not included)

So I've been saying that adventures advance via action, mysteries advance via clues. That's obviously simplistic -- if for no other reason than that the term "Mystery-adventure" exists.

What I'm starting to think, though, is that in most mysteries, clues go beyond being pieces of a puzzle.

Imagine the stock setup of the office over the neon sign. The detective is just reaching for the scotch when the dame walks in. Missing husband, she says. So, it could unfold that he looks for clues to where the husband is, collects those clues one by one, and finds the husband.

That is sort of how the classic Agatha Christie setup is supposed to work. We know what happened, and all we need to know is who did it. We find out, we end the story. It can be as simple as ruling out the left-handers and those with a good alibi until there's only one logical suspect. Calling everyone together in the drawing room for the denouement optional.

What is more usual is that something changes with each clue. That the story advances in some way beyond the collection of plot coupons.

The detective discovers the husband was involved with the mob? The scope just got bigger. Detective discovers husband is a widower and the dead wife looked nothing like the dame who hired him? The question has changed. Detective finds a dead body? The stakes have changed, from missing husband to murder.

In each of these, it is exciting because the story itself is evolving.

A string of clues can lead to a change of location, but you can change location without the excuse of clues. Change is good, but if all that happens is you've moved from Chicago to Cincinnati, at some point the reader will experience it as motion for the sake of motion. Not motion that progresses the story.

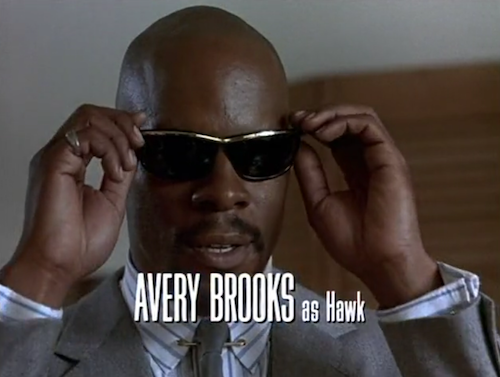

And there's one other exciting thing that can happen because of clues. And that's a change to the world. Spenser loved it when thugs would show up to beat him up; it meant that he was shaking the right trees. When the FBI sweeps in to take over the investigation you know the efforts of the protagonist have amounted to something -- and the story has moved to a definite new stage.

The problem I've got in how I've been telling the Athena Fox stories is that the clues are accretional. They aren't usually distinct things ("he's really left-handed!") but an emotional understanding that comes out of a gestalt of a culture and place.

Perhaps what bothers me is they feel too internal. Penny makes a realization that clarifies for her, personally, what is going on and what is at stake. It doesn't change the direction the outer story is moving. It doesn't change what anyone else does. She rarely gets a chance for a j'accuse. I've never managed to put her in a full-on Appleseed moment when she has to decide whether to shoot or not shoot based on everything she has learned up to that point.

Really, the way I've plotted the things, by the time she gets to the decision point there's only one obvious choice to make.

In any case, the fuzzy logic nature of the things and the process removes it from something the reader can have an illusion of solving with her. In a classic Perry Mason, all the facts are laid out for the viewer. They can solve the case themselves -- well, except for getting the witness to break down on the stand.

The other pole is what TVtropes calls "Bat Logic," where the chain of reasoning is shown but makes no sense. In that version, the fun is watching the detective work, not in trying to anticipate their findings yourself. Doctor Who and The Librarians also work within this space. In the case of the latter, supposedly this is real science and real art history but for the most part the science is just as rubber as Doctor Who, or Eureka, or Captain Planet.

Oddly enough, for all the rubber science in Doctor Who, it comes closest to playing by the rules. Every now and then, there's a biggie for which all the information was clearly presented to the viewer as well (and, usually, to the Companion who ends up solving it).

So that's two things to keep in mind for a mystery. Two things with a nearly inverse relationship; for a puzzle-solving, Ellery Queen Magazine style locked-room, transparency of the detection process is strongly wanted but a change to the status quo is not.

For mysteries that are part of an adventure or thriller, transparency can be waived, but the story is flatter and less interesting if the process of finding the clues doesn't cause the story to advance in other important ways.

Clues shouldn't just come after a fight or chase scene. They should inspire one.

No comments:

Post a Comment