..but give them what they want, not what they say.

If you are professional, you do the job they hired you for. Even if the client is screaming at you, even if the show stinks, you sit there and you finish the job you contracted on.

But I've worked with more than a few people who think the job stops there. That if the client is an idiot and wants them to turn off all the lights in the middle of the act, turn the subwoofer to eleven and turn all the wedges backwards...then you just do it, and rationalize the horrible lighting and sound by knowing you did exactly what was asked of you.

Well, we are not golems. This kind of petty exact-letter-of-the-orders crap is not professionalism. Find a way to get the client what they really want; the kind of look, the kind of sound, and talk them into how the equipment has to be set up to do it -- even if you have to go behind their backs to do it.

Just remember; they have the last say. Their vision is what belongs on stage, not ours. If they were after the look of a blacklight effect, then we should get as close as possible, but if their artistic goal was actually to kill the lights on the performers and leave the audience puzzled, then we should respect that.

And they might know what they are doing. We are not wizards. We don't know everything, and we can have off days, too. So before you nod and smile and pretend to turn the guitar up without actually touching a fader, take a long hard look at what is actually going through the sound system. And maybe even try nudging that fader. Because it could be the client has a better idea of what that band on that day really needs.

Sure, it is harder to fight for a good show. Sure, it is attractive to take your anger at being yelled at out on the client by sitting there in your self-righteous sulk and letting the unhelmed ship plunge directly towards the pier.

But at the end of the night, the paying audience, the gods of theater, your own artistic growth, and yes even the annoying client; they all deserve better from you.

And that's professionalism.

(No; the show I just concluded was pretty much a pleasant experience. And the rest of the tech staff mouthed off a lot backstage, but they still put out the best performance they could manage. But they reminded me of how many times I have seen techs cross that line. And how many times I've let myself cross it, as well.)

Tricks of the trade, discussion of design principles, and musings and rants about theater from a working theater technician/designer.

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

Look Ma, no wires.

I'm having to put together a proposal fast for twelve-plus channels of wireless lavalier mics.

The options haven't gotten better in the way I had hoped, not yet. Only one company so far seems to have brought a digital system into the middle price range, and it is a gigahertz system. I'm not interested. My XBee work has informed me far too well of the difficulties in punching through a reliable signal at 2.4 gHz.

The way things seem to be settling out now, is the price ranges correspond to a set of assumptions from the manufacturers. At the low end, they are generally fixed-frequency systems. Through both low and middle, the manufacturers seem to assume their biggest problem is the users are idiots; so all the effort is towards choosing compatible bands for you. With the result being you really can't use more than one system in the same space at the same time, not reliably. You must purchase a system pre-built with two lavs or eight hand-helds or whatever other package deal they have.

In the high middle of the price range are, finally, systems that are properly programmable, as well as being in wireless bands that are going to remain open for at least part of the next decade, full diversity, standard batteries, etc. So this range starts at maybe $500 a channel and progresses up to the low $1,000 range.

You have to jump up to the low end of the high-end gear, and very much break the $1K per channel of wireless cost group, before you get any of the recent work in adapting to the FCC's latest moves. And these aren't digital. They are other clever ways to shrink the bandwidth and deliver more effective channels in the limited frequency ranges still available.

And some of them are very clever. Top-line Shures can get you fifty microphones jammed into the bands available, and still let you run IEMs for the pit and wireless headsets on your backstage crew.

Thing about Shure is, once you leave their flagship gear -- any time you find an "X" as part of the model name, or the dreaded "PG," -- their quality takes a huge drop-off. Many working audio techs don't know this because they have only worked with Shure; they haven't had the experience of comparing the Shure SLX with similarly-priced units from other manufacturers. To them, the SLX behaves just like they expect; like a Shure you didn't spend quite enough money on.

I'm still looking at Audio-Technica, and even Electro-Voice, but even outside of being in frequency bands the FCC already has in their gunsights, and other issues, they just don't offer on paper anything remarkably better than the Sennheisers. And I know the sennies very well, and can speak to both their peccadilloes and their general reliability.

So I'm probably going to have to recommend purchasing something pretty similar to what I was already in position to rent to them. Sigh.

The options haven't gotten better in the way I had hoped, not yet. Only one company so far seems to have brought a digital system into the middle price range, and it is a gigahertz system. I'm not interested. My XBee work has informed me far too well of the difficulties in punching through a reliable signal at 2.4 gHz.

The way things seem to be settling out now, is the price ranges correspond to a set of assumptions from the manufacturers. At the low end, they are generally fixed-frequency systems. Through both low and middle, the manufacturers seem to assume their biggest problem is the users are idiots; so all the effort is towards choosing compatible bands for you. With the result being you really can't use more than one system in the same space at the same time, not reliably. You must purchase a system pre-built with two lavs or eight hand-helds or whatever other package deal they have.

In the high middle of the price range are, finally, systems that are properly programmable, as well as being in wireless bands that are going to remain open for at least part of the next decade, full diversity, standard batteries, etc. So this range starts at maybe $500 a channel and progresses up to the low $1,000 range.

You have to jump up to the low end of the high-end gear, and very much break the $1K per channel of wireless cost group, before you get any of the recent work in adapting to the FCC's latest moves. And these aren't digital. They are other clever ways to shrink the bandwidth and deliver more effective channels in the limited frequency ranges still available.

And some of them are very clever. Top-line Shures can get you fifty microphones jammed into the bands available, and still let you run IEMs for the pit and wireless headsets on your backstage crew.

Thing about Shure is, once you leave their flagship gear -- any time you find an "X" as part of the model name, or the dreaded "PG," -- their quality takes a huge drop-off. Many working audio techs don't know this because they have only worked with Shure; they haven't had the experience of comparing the Shure SLX with similarly-priced units from other manufacturers. To them, the SLX behaves just like they expect; like a Shure you didn't spend quite enough money on.

I'm still looking at Audio-Technica, and even Electro-Voice, but even outside of being in frequency bands the FCC already has in their gunsights, and other issues, they just don't offer on paper anything remarkably better than the Sennheisers. And I know the sennies very well, and can speak to both their peccadilloes and their general reliability.

So I'm probably going to have to recommend purchasing something pretty similar to what I was already in position to rent to them. Sigh.

Saturday, January 24, 2015

MY smart phone rant

As a Sound Engineer for musical theater, I already had reason to hate the new smart phones and similar devices. Their market is so much more powerful, chunk after chunk of the ever-shrinking bandwidth needed for wireless microphones is going there as the spineless FCC follows every other Federal agency burdened with "protecting" a natural resource.

And in my opinion, this is a bad trade-off. If you want to watch a movie on your phone, you can transfer the file at home, using a wire or available pipe. You don't have to have a unique media pipeline -- because there is no option for the actor in a musical to reach the sound board with their voice. There's no equivalent of a flash drive for them. It has to be real-time streaming or the musical is going to sound very, very strange.

But I've been riding BART and Muni a lot this week, and I'm seeing something new. I'm seeing a lot of people who are crammed into too-small seats on the lurching cars of crowded trains, and you can't do creative work in that kind of condition. You can barely concentrate enough to read a book. So it makes sense that all these people (a good two out of three, at least to my jaundiced eye) are on their smart phones. And the ones I can see over the shoulder are browsing forums or flipping through music, listening to a couple seconds then skipping to something else. Bandwidth city.

Oh, there's a few who are texting. A few probably posting to forums. And I've met them, both at work where some of my bosses and co-workers have sent replies from whatever transit nexus or automobile or dinner date or other meeting they are at.

And you know what? As content, those texts suck. I almost never get a useful answer for the work that needs to be happening. Between the limitations of the texting format and the much greater limitations of the situation (and the implicit belief in multi-tasking behind it), the information content ranges from minimal to negative. I can not BEGIN to list how many times we've wasted hours hanging lights only for Mr Too Busy To Do Anything But Send a Text to finally breeze in only to declare "That's not what I thought we were saying at all!"

Same for forum posts. There's a buttload of the content now on the interwebs that is feel good and metwo posts. And this is why. People who aren't in a position where they can be analytical, but still want to contribute. And we've constructed this social media edifice that claims that every meandering self-indulgent blog is Worthy and every fly-by night posting actually adds something to human knowledge.

I spit on these phones. Because they aren't constructed for creative work. Not deep, meaningful work. They are constructed for the illusion of work, while they do their best to suck you in to a care-free life of consume, consume, consume. They are the tools and vanguard of a movement to retake the Internet and move as many as possible back to the model of one licensed creator to ten thousands grub-like consumers (but with plentiful cash in hand).

And in my opinion, this is a bad trade-off. If you want to watch a movie on your phone, you can transfer the file at home, using a wire or available pipe. You don't have to have a unique media pipeline -- because there is no option for the actor in a musical to reach the sound board with their voice. There's no equivalent of a flash drive for them. It has to be real-time streaming or the musical is going to sound very, very strange.

But I've been riding BART and Muni a lot this week, and I'm seeing something new. I'm seeing a lot of people who are crammed into too-small seats on the lurching cars of crowded trains, and you can't do creative work in that kind of condition. You can barely concentrate enough to read a book. So it makes sense that all these people (a good two out of three, at least to my jaundiced eye) are on their smart phones. And the ones I can see over the shoulder are browsing forums or flipping through music, listening to a couple seconds then skipping to something else. Bandwidth city.

Oh, there's a few who are texting. A few probably posting to forums. And I've met them, both at work where some of my bosses and co-workers have sent replies from whatever transit nexus or automobile or dinner date or other meeting they are at.

And you know what? As content, those texts suck. I almost never get a useful answer for the work that needs to be happening. Between the limitations of the texting format and the much greater limitations of the situation (and the implicit belief in multi-tasking behind it), the information content ranges from minimal to negative. I can not BEGIN to list how many times we've wasted hours hanging lights only for Mr Too Busy To Do Anything But Send a Text to finally breeze in only to declare "That's not what I thought we were saying at all!"

Same for forum posts. There's a buttload of the content now on the interwebs that is feel good and metwo posts. And this is why. People who aren't in a position where they can be analytical, but still want to contribute. And we've constructed this social media edifice that claims that every meandering self-indulgent blog is Worthy and every fly-by night posting actually adds something to human knowledge.

I spit on these phones. Because they aren't constructed for creative work. Not deep, meaningful work. They are constructed for the illusion of work, while they do their best to suck you in to a care-free life of consume, consume, consume. They are the tools and vanguard of a movement to retake the Internet and move as many as possible back to the model of one licensed creator to ten thousands grub-like consumers (but with plentiful cash in hand).

Laser Rifles and Dying Fairies

Not, not "Wizards, The Musical" (which one day, in some other life, I would love to have a part in producing).

I took a short job in The City -- for low enough pay a third of it is going to pay BART fare -- and once again an application came up for a DuckLight. Which is currently in the form of a PCB being manufactured in China. That is, the prototype board is. I figure there's about a 50% chance the first board will actually work correctly.

Once again, I would have saved a lot of time if I could have just reached into my kit and pulled one out. But also, once again, I hadn't imagined anything like this application until it came long.

Tinkerbell. There's a spot in the musical where Tink needs to go into her little house and stay there for a while. I had already planned for one of the default animations on the DuckLight to be a flicker or shimmer, but I didn't even know why I wanted that. Now I do. Dial up a nice Tinkerbell green and the effect is half-way there.

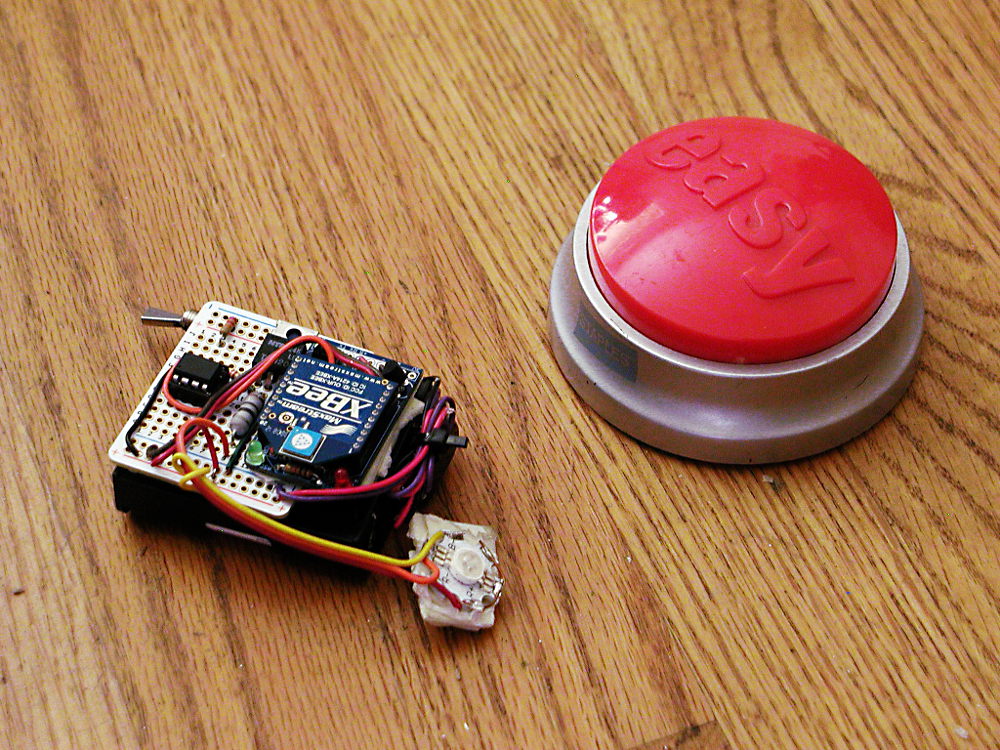

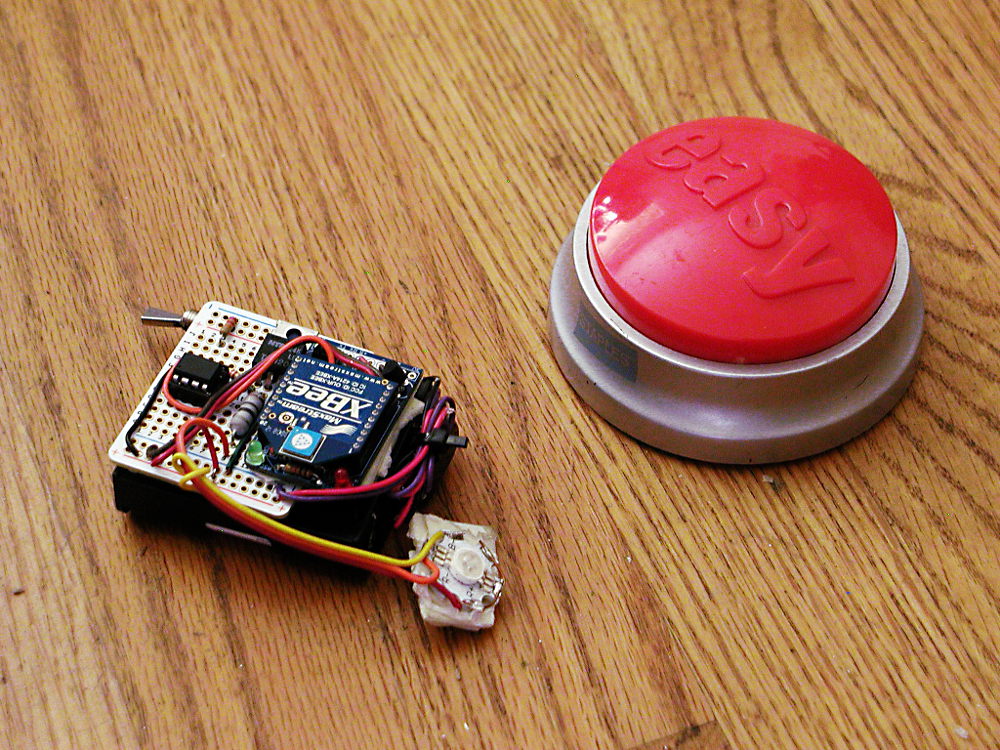

Only half-way, because this production is children's theater. No onstage actor is going to be able to hit a switch. So it needs the next element, the next board up in my Eagle-and-fab list; the XBee backpack.

Only half-way, because this production is children's theater. No onstage actor is going to be able to hit a switch. So it needs the next element, the next board up in my Eagle-and-fab list; the XBee backpack.

Well, I did pull a morning of very swift soldering, and set up a single-channel AVR-controlled Cree and attached an XBee to it in line-passing mode. There was some strangeness going on with lines floating or automatically resetting or something but by adding a double-click detect I finally got it reliable enough to use it over the closing performances.

Otherwise Tink is being played by a laser. Which still makes me uncomfortable, even though I opened up the beam focus until the power is much spread out. To hit his targets the follow-spot operator went and attached the laser to three-foot long stick of wood that he braces against his shoulder. Naturally I took to calling this contraption his "Laser Rifle."

Otherwise Tink is being played by a laser. Which still makes me uncomfortable, even though I opened up the beam focus until the power is much spread out. To hit his targets the follow-spot operator went and attached the laser to three-foot long stick of wood that he braces against his shoulder. Naturally I took to calling this contraption his "Laser Rifle."

Being one of the bargain bulk optical goods from the industrious young engineers in Shanghai, this particularly laser diode is not stable enough, cooled enough, or otherwise suitable for leaving on for longer than a few seconds at a time. As a stop-gap, I put an AVR-powered switch on it that randomly blinks it off for half a second or so every few seconds. That seems to help, but I'm betting I'll still be out a laser diode before the show closes.

The blinking looks quite natural and Tink-like. Particularly tonight's performance. Right after Wendy said, "Wouldn't you say so, Tinkerbell?" the light blinked several times in quick succession as if Tink was making an acerbic reply.

Here's the full circuit in better light, by the way:

The 8-pin dip is the ATtiny85 running the random blink routine. The Tip-120 switches laser power, with a blinkenlight wired in parallel as a status monitor. Another one monitors the battery connection, which is switched on and off by the momentary button. That's the nice thing about these AVR's; supply power, and it boots up softly in milliseconds and starts running the program loop.

This was all in all another informative show. I need that serial Xbee connection for reliable triggering, and this makes twice now that 3 watts of RGB was a little marginal. Unfortunately the jump to 10 watts of LED power brings in a whole new level of current regulator and thermal management complexity.

I took a short job in The City -- for low enough pay a third of it is going to pay BART fare -- and once again an application came up for a DuckLight. Which is currently in the form of a PCB being manufactured in China. That is, the prototype board is. I figure there's about a 50% chance the first board will actually work correctly.

Once again, I would have saved a lot of time if I could have just reached into my kit and pulled one out. But also, once again, I hadn't imagined anything like this application until it came long.

Tinkerbell. There's a spot in the musical where Tink needs to go into her little house and stay there for a while. I had already planned for one of the default animations on the DuckLight to be a flicker or shimmer, but I didn't even know why I wanted that. Now I do. Dial up a nice Tinkerbell green and the effect is half-way there.

Only half-way, because this production is children's theater. No onstage actor is going to be able to hit a switch. So it needs the next element, the next board up in my Eagle-and-fab list; the XBee backpack.

Only half-way, because this production is children's theater. No onstage actor is going to be able to hit a switch. So it needs the next element, the next board up in my Eagle-and-fab list; the XBee backpack.Well, I did pull a morning of very swift soldering, and set up a single-channel AVR-controlled Cree and attached an XBee to it in line-passing mode. There was some strangeness going on with lines floating or automatically resetting or something but by adding a double-click detect I finally got it reliable enough to use it over the closing performances.

Otherwise Tink is being played by a laser. Which still makes me uncomfortable, even though I opened up the beam focus until the power is much spread out. To hit his targets the follow-spot operator went and attached the laser to three-foot long stick of wood that he braces against his shoulder. Naturally I took to calling this contraption his "Laser Rifle."

Otherwise Tink is being played by a laser. Which still makes me uncomfortable, even though I opened up the beam focus until the power is much spread out. To hit his targets the follow-spot operator went and attached the laser to three-foot long stick of wood that he braces against his shoulder. Naturally I took to calling this contraption his "Laser Rifle."Being one of the bargain bulk optical goods from the industrious young engineers in Shanghai, this particularly laser diode is not stable enough, cooled enough, or otherwise suitable for leaving on for longer than a few seconds at a time. As a stop-gap, I put an AVR-powered switch on it that randomly blinks it off for half a second or so every few seconds. That seems to help, but I'm betting I'll still be out a laser diode before the show closes.

The blinking looks quite natural and Tink-like. Particularly tonight's performance. Right after Wendy said, "Wouldn't you say so, Tinkerbell?" the light blinked several times in quick succession as if Tink was making an acerbic reply.

Here's the full circuit in better light, by the way:

The 8-pin dip is the ATtiny85 running the random blink routine. The Tip-120 switches laser power, with a blinkenlight wired in parallel as a status monitor. Another one monitors the battery connection, which is switched on and off by the momentary button. That's the nice thing about these AVR's; supply power, and it boots up softly in milliseconds and starts running the program loop.

This was all in all another informative show. I need that serial Xbee connection for reliable triggering, and this makes twice now that 3 watts of RGB was a little marginal. Unfortunately the jump to 10 watts of LED power brings in a whole new level of current regulator and thermal management complexity.

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

Lot of work for so little pay

Inventoried stock and ordered the remainder for the next round of Stage Lights. Also reminded the purchaser I was barely covering expenses on them and soon I'd have to charge more.

Struggled some more with parts libraries in Eagle. The software has been through some changes recently and some of the more common suggestions found online no longer work. But I got it together and sent off an order for the first try at a board to OSHpark.

Inventoried my Aliens Grenade supplies, made up an order for new material, and sat down with a bunch of snapcaps and shotshells to check dimensions. Watching snippets of the movie again. I am increasingly of two minds about my design.

There's almost a fanon when you get to stuff like this; how it may have actually looked in the movie, and how prop-makers are tending to make them look these days. Aliens has a bit of that; the original Pulse Rifles were painted brown, but they read olive drab under the lighting of the movie. So which is more accurate? The actual color of the prop, or the color the prop appeared in the movie?

In the case of the grenades, there are sadly few high-resolution images, and few documented screen-used with decent images available. So one could make in a sense two different arguments; one for what the prop-makers probably provided, and what is therefor most accurate to a world in which a film was made about a bunch of space marines. And one for what is just at the verge of visibility, possibly hidden in blur and lighting effects; the world in which Weyland-Utani managed to get a bunch of them killed on a remote colony world.

In re the outer world, I have more than strong suspicions that the grooves were made with a thread-cutting tool, and are probably v-shaped. The spring-loaded trigger, of which there were unlikely more than one or two to begin with, was top-loaded. The nose is a simple chamfer and there is no "nose ring." And the cap was off-white, painted in various colors (seemingly red, dark blue, a rather washed-out green, and perhaps one or two in yellow), with a strip of teflon plumbing tape or a hand-painted white line. Oh, yes; and I have reason to believe there was a fairly large cut-out in the bottom, with the primer sticking out like a very short lamp post.

In the inner, diagetic world, these have more distinction in their markings. My head canon is that originally the caps were shaped differently to reflect the various loads, and as well some of the bodies are distinctive. Manuals and other materials were released on the basis of those models, but in the usual business of military contract bidding they ended up sharing molds and the items issued at the time of the film had lost some of those distinctions. And furthermore, GI's of any generation are playful, and once they found out the protective caps were interchangeable, would start putting them on randomly in whatever suited their own color/fashion sense.

And at some nearly orthogonal angle to either of these directions of approach, are the prop-maker's aesthetics. The major reason to keep those in mind is because one cosplayer may have props from more than one supplier. And more than one cosplayer may appear in the same picture. So if everyone is making their M51A's a bright baby blue, it makes a certain sense to follow suit.

The major elements found in fan-made grenades are however varied. Some have the tree-stump firing pins, others look more shotgun-like. Some have chamfered noses, some have rounded noses. However, almost all have squared-off grooves.

Which leaves me basically floundering between two untenables; follow the best guess of the best information and end up with a result that doesn't meet expectation: or do what fulfills my personal aesthetic judgment and is somewhat defensible both diagetically and historically -- but only somewhat, as the design combines elements I can not be sure of with elements I am reasonably certain are wrong.

Oh, yes. And I also got another reweld mentioned at me. A ZB-30, which from a brief look appears insane.

Struggled some more with parts libraries in Eagle. The software has been through some changes recently and some of the more common suggestions found online no longer work. But I got it together and sent off an order for the first try at a board to OSHpark.

Inventoried my Aliens Grenade supplies, made up an order for new material, and sat down with a bunch of snapcaps and shotshells to check dimensions. Watching snippets of the movie again. I am increasingly of two minds about my design.

There's almost a fanon when you get to stuff like this; how it may have actually looked in the movie, and how prop-makers are tending to make them look these days. Aliens has a bit of that; the original Pulse Rifles were painted brown, but they read olive drab under the lighting of the movie. So which is more accurate? The actual color of the prop, or the color the prop appeared in the movie?

In the case of the grenades, there are sadly few high-resolution images, and few documented screen-used with decent images available. So one could make in a sense two different arguments; one for what the prop-makers probably provided, and what is therefor most accurate to a world in which a film was made about a bunch of space marines. And one for what is just at the verge of visibility, possibly hidden in blur and lighting effects; the world in which Weyland-Utani managed to get a bunch of them killed on a remote colony world.

In re the outer world, I have more than strong suspicions that the grooves were made with a thread-cutting tool, and are probably v-shaped. The spring-loaded trigger, of which there were unlikely more than one or two to begin with, was top-loaded. The nose is a simple chamfer and there is no "nose ring." And the cap was off-white, painted in various colors (seemingly red, dark blue, a rather washed-out green, and perhaps one or two in yellow), with a strip of teflon plumbing tape or a hand-painted white line. Oh, yes; and I have reason to believe there was a fairly large cut-out in the bottom, with the primer sticking out like a very short lamp post.

In the inner, diagetic world, these have more distinction in their markings. My head canon is that originally the caps were shaped differently to reflect the various loads, and as well some of the bodies are distinctive. Manuals and other materials were released on the basis of those models, but in the usual business of military contract bidding they ended up sharing molds and the items issued at the time of the film had lost some of those distinctions. And furthermore, GI's of any generation are playful, and once they found out the protective caps were interchangeable, would start putting them on randomly in whatever suited their own color/fashion sense.

And at some nearly orthogonal angle to either of these directions of approach, are the prop-maker's aesthetics. The major reason to keep those in mind is because one cosplayer may have props from more than one supplier. And more than one cosplayer may appear in the same picture. So if everyone is making their M51A's a bright baby blue, it makes a certain sense to follow suit.

The major elements found in fan-made grenades are however varied. Some have the tree-stump firing pins, others look more shotgun-like. Some have chamfered noses, some have rounded noses. However, almost all have squared-off grooves.

Which leaves me basically floundering between two untenables; follow the best guess of the best information and end up with a result that doesn't meet expectation: or do what fulfills my personal aesthetic judgment and is somewhat defensible both diagetically and historically -- but only somewhat, as the design combines elements I can not be sure of with elements I am reasonably certain are wrong.

Oh, yes. And I also got another reweld mentioned at me. A ZB-30, which from a brief look appears insane.

Monday, January 19, 2015

CAD Woes

Trying to get the PCB ordered on my prototype "DuckLight." The first Eagle layout looked pretty good, but it seemed possible to shrink the board's footprint until it was only 2xAAA wide. Which you can run on, but it runs the LEDs a little cold.

Anyhow, I shrunk the layout and ran traces by hand. I was also conscious of the potential difficulties in soldering SMDs so I made a point of holding the traces far outside of the pads of those parts. So that took a couple of evenings. But got it down to one via (well, I also ended up omitting a duplicate VCC on the second header. It would have required multiple vias in order to get the connection.)

I used a part with internal connections (a tactile switch) as a jumped in one spot, and Eagle kept flagging it. So I went to the forums for the first time with a question. And it turns out not only have lots of people asked about this, there is no current solution.

But then I went to order the parts to make sure the ones in the CAD were actually available stock. I'd used the SparkFun Eagle library in several places, and you'd think this would be a shoe-in, right? But no. The part in their library doesn't actually have an analog in their store.

They did have something in their store that I could modify the package to, however. And after a bit of struggling re-routing around the new (and larger) dimensions, I had confirmation of available parts.

The final DRCs, and Eagle starts throwing up mask errors. Turns out that, yes once again, many of the library parts I was using have a silkscreen that goes over the copper traces. Which can be a problem at smaller fab houses that don't have the software to fix this on the fly. So back once again to the package designs, now to edit all the silkscreens.

Nice of various people to make libraries available to everyone, but really, could they adhere a little closer to reality?

Anyhow, I shrunk the layout and ran traces by hand. I was also conscious of the potential difficulties in soldering SMDs so I made a point of holding the traces far outside of the pads of those parts. So that took a couple of evenings. But got it down to one via (well, I also ended up omitting a duplicate VCC on the second header. It would have required multiple vias in order to get the connection.)

I used a part with internal connections (a tactile switch) as a jumped in one spot, and Eagle kept flagging it. So I went to the forums for the first time with a question. And it turns out not only have lots of people asked about this, there is no current solution.

But then I went to order the parts to make sure the ones in the CAD were actually available stock. I'd used the SparkFun Eagle library in several places, and you'd think this would be a shoe-in, right? But no. The part in their library doesn't actually have an analog in their store.

They did have something in their store that I could modify the package to, however. And after a bit of struggling re-routing around the new (and larger) dimensions, I had confirmation of available parts.

The final DRCs, and Eagle starts throwing up mask errors. Turns out that, yes once again, many of the library parts I was using have a silkscreen that goes over the copper traces. Which can be a problem at smaller fab houses that don't have the software to fix this on the fly. So back once again to the package designs, now to edit all the silkscreens.

Nice of various people to make libraries available to everyone, but really, could they adhere a little closer to reality?

DONE!

If I ever do a reweld again, I am never going to weld the bolt into the receiver. The true cost of that became clear during final assembly. There are so many parts that require the bolt be moved out of battery in order to put them together.

Okay, sure, I could have simply omitted much of the unseen, internal hardware, and just fixed bits like the charging handle in place with epoxy. But I had come this far with real steel, it seemed a shame to do that.

Plus, if you are going that route, having a bolt-substitute that travels means you can cock and dry-fire.

The fake bolt got in my way not just in putting on the last parts, but even in drilling some of the last holes. It also stands just slightly proud where the magazine lips sit, and won't quite let the magazine go far enough in to engage the magazine catch. Which I could have fixed, but I really needed to finish this project and move on.

So here it is:

That out-of-period hex nut is my imperfect solution to securing the barrel shroud lever. In the original, the stem was pounded down to make a rivet. I milled the broken stub flat, drilled a hole, and tapped it for a metric stud, which is fixed in with Locktite.

For the top sight, I drilled for friction pins, but ended up seating them with Locktite too when the holes got a little chewed up. The fake bolt kept catching on the drill bit. So all in all, I spent about four hours on the mill, mostly using it as a stable platform to align everything for the last couple of mounting holes.

And here is a shot looking more-or-less from the good end (taken in poor light, sorry):

The repaired part more-or-less blends in; the rest of the metal is a pretty good mix, from the somewhat rust-colored barrel (with most of the factory bluing worn off) to the flat black paint on the magazine. And all of the other parts are original, and essentially un-touched by my process.

Okay, sure, I could have simply omitted much of the unseen, internal hardware, and just fixed bits like the charging handle in place with epoxy. But I had come this far with real steel, it seemed a shame to do that.

Plus, if you are going that route, having a bolt-substitute that travels means you can cock and dry-fire.

The fake bolt got in my way not just in putting on the last parts, but even in drilling some of the last holes. It also stands just slightly proud where the magazine lips sit, and won't quite let the magazine go far enough in to engage the magazine catch. Which I could have fixed, but I really needed to finish this project and move on.

So here it is:

That out-of-period hex nut is my imperfect solution to securing the barrel shroud lever. In the original, the stem was pounded down to make a rivet. I milled the broken stub flat, drilled a hole, and tapped it for a metric stud, which is fixed in with Locktite.

For the top sight, I drilled for friction pins, but ended up seating them with Locktite too when the holes got a little chewed up. The fake bolt kept catching on the drill bit. So all in all, I spent about four hours on the mill, mostly using it as a stable platform to align everything for the last couple of mounting holes.

And here is a shot looking more-or-less from the good end (taken in poor light, sorry):

The repaired part more-or-less blends in; the rest of the metal is a pretty good mix, from the somewhat rust-colored barrel (with most of the factory bluing worn off) to the flat black paint on the magazine. And all of the other parts are original, and essentially un-touched by my process.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)