Here’s the second image. A Turkish powder magazine explodes, delivering the final indignity to the creaking, discolored ruins of Athen’s heart.

Two different cities, two different monuments, two different sets of problems in archaeological restoration and the often complex relationship between a modern nation and their cultural heritage.

Knossos is terribly underfunded. It seems strange at first glance. Athens is scarred by their economic woes; abandoned buildings with gaping windows like rotting teeth in faces covered with graffiti, pavements scored with broken walks and open drains and drifts of garbage. By contrast Heraklion, (from the harbor at least), is clean and modern and wears proudly the remodeling for the 2004 Summer Olympics. Even the tourists look wealthier.

(The contrast is even stronger at Chania. This is basically a sea-side resort town. The history underfoot is barely remarked upon; in a long dockside strip of eateries and bars and trinket shops no signage showed and only a handful of people seemed to know there was a full replica Minoan sailing vessel on display nearby -- among the other archaeological and historical treasures.)

Work has all but stopped at the site of the Palace of Knossos. Down at the Heraklion Museum they speak proudly of the restoration efforts on their collection (which as with so many begins with removing the efforts of the previous generation). But at Knossos itself, the best description of the present efforts is stabilization. Keeping it from disintegrating further before the money for actual work flows in again.

The site is under-documented by the standards of the new Acropolis Museum. But there is some justification in calling that a special case. Knossos is layered, an archaeological palimpsest and a restoration bricolage, and that is part of the problem.

Cleverly, the Knossos signage cleaves to an essentially Sir Arthur Evans narrative. Although this is couched with qualifiers like, “Evans called this...” or even, “Evans mistakenly believed...” the singular narrative through-line is Knossos as Evans and his generation experienced it and understood it.

It could be argued that this is the best approach for most visitors. It is one step more honest than simply saying, “This is a Lustral Basin” but it doesn’t drag the visitor into the full depths of complexity and confusion.

In the States, the age at which a building can apply for protected landmark status is the ripe old age of fifty. Archaeology can be done — archaeology has been done — where some of the original participants are still alive.

So what is the best way to approach a palimpsest like, say, the Koules guarding the Heraklion harbor? Restore it to the Venetian fort that stood so long, or the Ottoman modifications when they finally took it and, too, produced a grim history in and around it? Restore whatever mute evidence the Second Wold War may have left, or restore it to the Byzantine walls? And do you keep the moule, or do you re-float the Venetian ships that made its foundation and make them your exhibit?

In short, one could almost defend presenting Knossos as the historical efforts of Sir Arthur Evans. But let’s contrast.

There was a Mycenaean complex (probably a fort) on the Acropolis and Cyclopian walls about the heights of The Rock. There were several generations of earlier temples. And there were later, largely civil uses of the centerpiece structure. But against all of this the Periclean Parthenon is both the architectural and artistic height of all the constructions that site has seen, and the symbolic centerpiece of the Athenian democracy and the Greek Classical world.

So it makes sense to restore towards this Ur-Acropolis. But unlike Knossos, where the multiple levels of occupation and (sometimes questionable!) “restoration” are ill-documented at the site, the Parthenon and particularly the new Acropolis Museum carefully and clearly indicate the layers of provenance involved.

(The Provenience of the parts of the Parthenon are, unlike in almost every other archaeological context, quite simple. At least, for the sculpted facade. In modern parlance, the provenience of an artifact is the exact find location. In this case, the sculptures started life on the building. And not in the British Museum, as the exhibits at the Acropolis Museum take pains to point out!)

At the site itself, every tiny fragment of column has been carefully measured and 3D modeled and the correct location determined in the world’s largest picture puzzle. Where the originals are unavailable (lost to time or to Lord Elgin’s luggage) replacements are provided in plaster cast and fresh white marble.

This allows for both appreciation of the total aesthetic — the building as it would have been — and understanding of what parts are historical and what parts (the shining white parts) are not. It is something that Knossos could have benefitted from, except there the story is far more complicated. How does one mark a Dolphin Fresco that Evans had on a wall and modern papers believe was more likely on the floor, and in any case is in the relative safety of a museum with only a replica on site?

The thing is, though, Evans was right. Not in his guesses, but science marches on. Not in his reconstruction efforts — which like earlier efforts at the Acropolis eventually damaged the stone — but, again, the science of restoration marches on. He was right in doing what he did at the time he did it. The site would be gone now, farmland or a condo, if he hadn’t made it something those Victorians could admire and paint and have their photographs taken on as they lined up in the long coats and top hats along some crumbling wall.

There is something to be said for the aesthetics of a ruin. But you get more public attention, more tourist dollars, more help in preservation, if you have something that looks more like a building. I am tempted to say Knossos doesn’t go far enough. There is a virtual replication in the cloud and a place in town where you can rent a tablet and a VR headset and walk around a fully-restored building, bull-leapers and all.

Imagine if something like that was available on site! I’ve seen this. In Berlin (at the grand Museum für Naturkunde) there is a paleontological exhibit where by standing behind a viewing class the dry bones can be clothed in muscle and skin and feathers and placed in their natural habitat. There is an effort somewhere that has a huge collection of those now stark white marble statues that with another press of a button clothes them with light, bringing back the colours of history.

(The new Acropolis Museum makes crafty compromise by displaying in air-conditioned safety the actual Kouros and Kore from the Parthenon but placing beside them small samples of contemporary reconstruction of the original paint job.)

Above all, however, both these places are symbols. Knossos is merely one photogenic touchstone (when taken from exactly the right angle and cropped ever so carefully; the Evans restorations are, when all is said and gone, pitifully small bits of wall and sequences of column). It stands along side of reproductions of the Dolphin Frescoes and Bull Leaper and Bull Rhyton and so on (which also are rather more Victorian restoration than original artifact).

(It is also informative that the “Mask of Agamemnon,” that in many circles is the emblematic and much-reproduced artifact of that peculiar juncture where the Classic and Homeric tradition meet the historical reality, is presented in Athens at the National Museum of Archaeology as just another shaft-grave death mask. But then, much as Knossos is a monument to Sir Arthur, the largest collection in Athens is assembled and presented as, "Here's what Schliemann dug up.")

The Minoans are today a way that Crete reinvents itself as something other than a backwater island in a nation with a broken economy. And of course a way to draw in the tourist dollar. Their imagery is everywhere (I say imagery because the actual artifacts are thin on the ground but reproductions are everywhere, from made-in-China caliber Phaistos Disk reproductions available at every other souvenir stand, to nicer hand-painted miniatures of the Prince of the Lilies, and — moving from not-so-sublime to worthy-of-ridicule — the Court Ladies fresco incorporated into the plastic banner on the Coke stands.)

But there’s no depth in it. No wearing of the mantle of the true progenitor of the Greek Miracle, or at least the past glory of a Minoan Thallasocracy. Now all there is, is the Minoan Bus-Ocracy (Minoan Lines, the most visible of the huge Bus Tour operations that plow through the place like Achilles and his ships on a “foraging” expedition against the defenseless villages of the Anatolian Coast. The tour buses are everywhere, the most visible part of a massive efficient machine that delivers door-to-door from airport to air-conditioned hotel to guided tour, and everything and everyone else must bend to accommodate them.)

It is simply presented as, “This is historical; look at it and be impressed.” The same can be said, alas, for the Cretan’s attempts to share their more recent cultural heritage with the world. “It is traditional,” they say, as if that is enough; no explanation, no context. I can stand on one foot and hum “Barnacle Bill” and call that traditional and it would be, if only for me. If they truly want people to engage with the historic folkcrafts or the nautical tradition or the terrible and inspiring stories of the Cretan Resistance, they need to provide more.

(At Arolithos Traditional Cretan Village they laud their open museum of “living history” displays. They even offer their vision of engagement; for ten Euros your kid can learn a Camp Runnamucka version of the mosaic work the Byzantines brought to such a high peak. But it stops there. One simplistic, one-way presentation. Don’t ask questions.)

What I’m saying is the curation is abysmal. There are few placards and those are uninformative, and to a man or woman the docents are both uniformed about the museum and its subjects and monumentally uninterested in either them or in the act of conversation itself. (Unfortunately this isn’t a peculiarity of museum staff. Shopkeepers also make you work for the privilege to give them your money.)

I do have to say that even the best of the Athenian museums also fall down a bit by world standards. There wasn’t a catalog number in sight. It was hard sometimes to even nail down era or collection. I’d be tempted to say this stems from the embarrassment of riches; the collections are so vast they can only present them in patterns, like “Pots that include an octopus in their decoration.” But that’s another discussion!

What really separates Athens in this sketch here is that the Parthenon is Athens. As Athena herself remains Athena Potnia, the patron saint and protector of the city. The Parthenon is not a place disconnected from current life, like the Palace of Knossos or even the Sinking of the “Elli”; it is effectively the Cathedral of the majority religion. (Not that is functional in any current rituals, or even connected to the professed and officially recognized faiths.)

And I have to stop here and say these aren’t unique issues.

Besides the radically different standards of different museums and monuments worldwide — no nation, no city is without fault — there are basic questions about preservation and accessibility that are not dissimilar to the problems a writer of history (or historical fiction) faces.

There are always market forces. What was important to Athens in the early twentieth century led to what the Parthenon is today. What was inspiring to the Victorians is — as had been the case many times in the past, from Napoleon back through to fifth Dynasty Egyptians — what led to the preservation of what we have today and the interest that raised generations of scholars who would go on to advance our current knowledge.

Monuments and museums have to chase the buck. They have to work within those blurry lines of dramatization and simplification. They have to speak to the viewer whether it is aesthetics or spiritual connection or lessons for the present or (the illusion of?) learning and/or self-actualisation. To do less is to lose the museum, the collection, the monument itself. Athens at least has state support for their grand symbol of the state, but even there money has to come in or the monument doesn't survive.

But beyond serving the needs of the archaeological and historical community, professional and amateur, the museum or monument should, I think, also serve the real needs of the public.

I would like to think the need of most of that public is the sense of transcendence of one’s own mortal lifespan; of being able to walk where the Poets had walked. Of having for a moment a grasp of the boundless. I’d prefer an interest in understanding a different people and different ways, if for no other reason because that helps us to lift our own blinders and for that moment see our own predictions and presumptions as if with alien eyes. But in any case it beats an interest in boasting rights (the selfie-taker infesting modern monuments would be utterly familiar in needs and process and rationale to the Victorians who went to Athens and Rome and, eventually, Crete.)

To speak to that majority audience you need to streamline. You may need to reconstruct or fill in (depending on the circumstance). You need in short to lie, to commit sins both of omission and confabulation.

But that still doesn’t keep me from wanting that other layer to be available. From wanting those access points, from catalog numbers to educated docents, that allow one to drill down beyond the repainted facade to something deeper. Instead my experience across Greece was one of active resistance.

There’s a whole other sideline here about folkloric crafts. There are thriving communities interested in, keeping alive, being inspired by, and otherwise practicing crafts from history or reconstructed from archaeology. It upset me that the points of access were almost nonexistent on Crete despite the several clever and fascinating folkways museums.

Take spinning and weaving. However. There was a small exhibit sponsored by some government agency trying to grow the market for Cretan silk that tried to produce a kit to let you try pulling silken threads from a cocoon yourself. Alas it was badly explained, poorly presented, and none of the exhibiters had any idea how it actually worked.

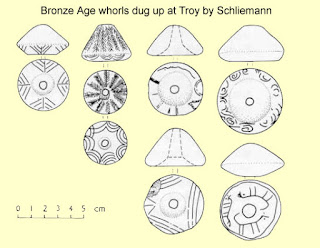

And, yes, as someone fascinated by the practicalities of daily life artifacts, it is disheartening to find at even a good museum — one that recognizes and labels loom weights and spindle whorls — the distinctive and informative linen-spinner’s bowl is left unremarked among a class of general household pottery. Or that a set of actual surviving clay tuyeres is simply labeled “tuyeres,” losing that brazen opportunity to talk about the ingenious period smelting practices.

But this should be no surprise. When the sleek mechanism is designed to ferry the tourist as smoothly and quickly as possible through the monument and into the gift shop, the very concept of dialog is anathema. Only a passive audience can be processed with efficiency. And the shame is that the audience seems largely satisfied. Whatever experience they were seeking, they seem to have gained it somewhere between the massive bus that made sure Cretan soil never touched their pristine footwear, and the hotel amenities that made it as much as possible like any other large hotel anywhere in the world.

The visitor who wants, needs, and can accept more (I saw one visitor at the National in Athens who was getting an expert lecture from his friend, another visitor -- a man I am almost certain was Eric Cline himself!) is the outlier. They have to fend for themselves. The visitor who has moved even further from the mainstream, like the growing groups of historical and folkloric re-creationists, is even more left with no easy access to what they were hoping to find.

And there is no simple answer to this. It is not a fault, per se. Certainly not one of any agency. It is merely a function of how things work, how they -- apparently -- must work, but certainly how they have currently evolved.

And for all of that said....yes, the material is still there, and I got something worthwhile from it.